On March 29, 2017 President Trump’s executive order established the President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis. New Jersey Governor Chris Christie (R) was appointed chair of the Commission and, although the list has not been finalized, Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker (R), North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper (D) and Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi (R) are expected to join as well. Administrative support for the Commission will be provided by the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP).

On Friday, the Office of Management and Budget released a document proposing to cut the ONDCP’s budget from $388 million to $24 million. These cuts would also eliminate grant programs, such as the High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas (HIDTA) Program and the Drug-Free Communities Support Program, on the basis that the programs are “duplicative of other efforts across the Federal government and supplant State and local responsibilities.”

The timing of both these events is significant. Including state leaders on a national commission, while cutting a federal office that coordinates federal drug policy, sends a clear message: state policy will steer the national drug control strategy, and not vice versa.

Examining how each of these leaders have approached the opioid crisis will offer insight into which policies the Commission is likely to consider and endorse. The Commission must identify existing federal funding, which includes the 21st Century Cures Act, to combat drug addiction and the opioid crisis; assess the availability of drug addiction treatment and overdose reversal; evaluate the effectiveness of prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs); review effectiveness of public educational messages on drug abuse; and review provider education and prescription practices. An interim progress report is due in 90 days (from March 29) with a final report due to the President by October 1, 2017.

What Will State Leaders Bring to the Commission?

Governor Baker has publicly stated, with respect to the Commission's purpose, “Our goal here is to collect as much information as we can through governors around the country and then incorporate that information into sort of a discussion document.”

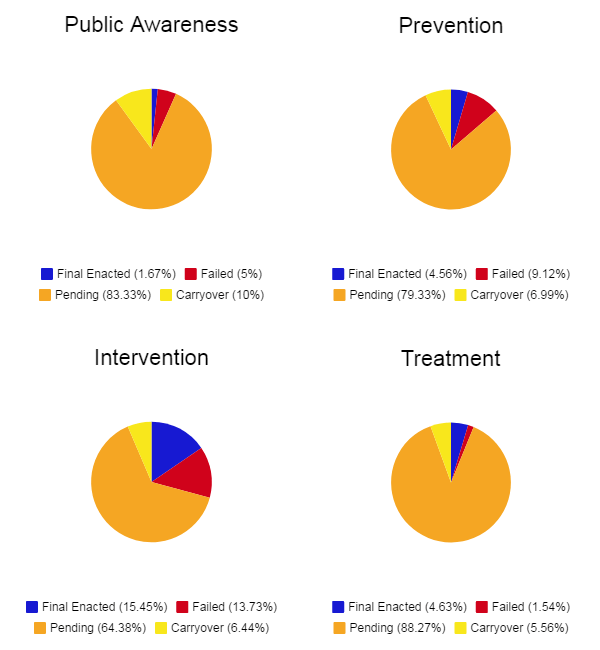

Governors Baker, Christie and Cooper have each focused on four distinct areas of drug abuse policy - prevention, intervention, treatment and public awareness. State legislatures have also been highly active in these four areas during the 2017 legislative session. Below is a breakdown of measures that have failed, were final enacted, are pending consideration or carried over into the 2018 legislative session.

Legislation aimed at intervention, such as modifying how prescription drug monitoring programs are used and establishing electronic prescribing requirements, has proved more successful than other forms of drug abuse policy. With respect to prevention, states have been introducing legislation aimed at opioid prescribing policies.

With this in mind, it is worth examining how and which policies Governors Christie, Baker and Cooper have supported in the past to assess what they will propose for the future.

Prevention

Governors Christie, Baker and Cooper have each favored limits on initial opioid prescriptions for acute pain and exemptions for cancer, palliative care and hospice care. Governor Baker initially favored a three-day limitation but eventually agreed to a seven-day limitation in Massachusetts’ H.B. 4056. Signed into law in March 2016, H.B 4056 became the first law of its kind in the nation. The following year Governor Christie’s S.B. 3 called for a five-day limitation. S.B. 3 was signed into law in February 2017, less than 30 days from its introduction. H.B. 243, which has garnered the support of Governor Cooper, also implements a five-day limitation. It is currently under consideration by the North Carolina General Assembly.

Governors Christie and Baker have also supported requiring health care practitioners to complete continuing education requirements for prescribing opioid drugs, learning about opioid alternatives for pain management and recognizing the risks and signs of opioid abuse before prescribing or dispensing.

Intervention

Governors Christie, Baker and Cooper have all supported mandated prescriber PDMP use requirements. S.B. 3 and H.B. 243 require a practitioner to review the PDMP when a Schedule II controlled substance or prescription drug is initially or continuously prescribed for three months or more for acute or chronic pain. H.B. 4056 requires registered PDMP participants to utilize the program each time a prescription for a Schedule II or III controlled substance is requested prior to issuing the prescription.

Treatment

Governors Christie and Cooper have also focused on promoting access to substance abuse treatment. For example, S.B. 3 removed prior authorization for the first 180 days of inpatient and outpatient treatment for a substance use disorder. Governor Cooper’s budget proposal calls for expanding Medicaid to 624,000 individuals and appropriating $12 million to community service programs for 2,500 people to combat opioid abuse.

Public Awareness

Governor Christie’s Reach NJ campaign established a website that includes information on resources for addiction treatment. H.B. 4056 required drivers’ education programs and public schools to have a policy educating students about the impact of addiction. Cities, towns, regional school districts, charter schools and vocational schools must also conduct annual screenings for substance use disorders. Governor Baker, in conjunction with the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, also launched the Stop Addiction in Its Tracks campaign, which featured TV ads warning parents about opioid misuse.

How States Have Responded to the Opioid Crisis

Enhancing PDMPs

PDMPs are statewide electronic databases that collect, monitor and analyze electronically transmitted prescription data submitted by pharmacies and practitioners. The data is used to aid state efforts in education, research, enforcement, prescription drug abuse prevention and curbing the practice of “doctor shopping.” Currently, 49 states, as well as D.C. and Guam, have an operational PDMP. Missouri is the one exception (although St. Louis County, St. Charles County, Ste. Genevive County and Cole County enabled PDMPs). Although nearly every state has a PDMP there is considerable variation in how they are used. At least 26 states and Guam require prescribers to check the PDMP (i.e. a “mandated use requirement”) before writing opioid prescriptions, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). A handful of states require the real-time reporting of dispensed controlled substances, while others have weekly or monthly reporting requirements. At least 40 states are engaged in interstate data sharing, allowing data from one state’s PDMP to be shared with another state.

Opioid Prescribing Limits and Pain Management

In March 2016, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) published guidelines revising how providers should assess pain and prescribe opioids. While not required, the guidelines recommend that prescribers limit initial prescriptions to a three-day supply or less for acute pain. States have sought to mandate these guidelines with varying degrees of success. Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New York and Rhode Island statutorily established seven-day requirements on initial prescriptions. A recent Delaware rule also established seven-day limitations and Ohio Governor John Kasich (R) announced his support of a rule that would follow suit. New Jersey’s five-day limitation is the strictest in the nation, according to the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Naloxone Access and Distribution

Naloxone hydrochloride (“naloxone”) is an opioid antagonist used to reverse an opioid overdose. It can be administered intranasally, through an autoinjector or via a needle or syringe. States have expanded naloxone access through third-party prescriptions and establishing Good Samaritan laws. Such laws provide immunity from arrest, charge or prosecution in the event of reporting an overdose or administering naloxone. To date, 46 states have enacted naloxone access laws. More than half of all states have also issued standing orders, allowing pharmacists to dispense naloxone without a prescription. Others have expanded naloxone access to first responders, schools and restaurants. Connecticut passed a law providing civil and criminal liability to anyone who administered naloxone. Subsequently, the city of Bridgeport, Connecticut increased its supply of naloxone to first responders. This led to Bridgeport firefighters administering naloxone an average of twice a day.

Access to Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT)

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is the use of medications (such as methadone, buprenorphine and naltrexone), in combination with counseling and behavioral therapies, to provide treatment for substance use disorders (SUD). According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), nearly 12 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries over the age of 18 have a SUD. A 2013 report by the American Society of Addiction (ASA) noted that although 28 states cover methadone, buprenorphine and naltrexone, the extent of coverage varies considerably. Forty-four states require prior authorization for buprenorphine while methadone is not typically subject to prior authorization. States have also established time, dosage and lifetime limits for buprenorphine. A total of 14 states have established a maximum daily dose of buprenorphine after six months or more of therapy, ranging from 8 to 16 milligrams, according to the ASA. In an effort to improve access to buprenorphine, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services increased the number of patients, from 100 to 275, which a doctor may treat with buprenorphine. However, physicians must still qualify for a physician waiver in order increase their patient limits. Eligible physicians are those that have prescribed buprenorphine to 100 patients for at least one year.

Attorneys General

Attorney General Pam Bondi (R) worked with the Florida Legislature in 2011 to pass H.B. 7095, which reduced the state’s “pill mills” and established stricter criminal and administrative penalties for doctors engaged in prescription drug trafficking. The CDC reports this led to a 50% decrease in oxycodone overdose deaths. Attorney General Bondi and Florida Governor Rick Scott (R) are currently supporting measures (S.B. 477 and S.B. 788) in the Florida Legislature that would increase penalties for trafficking fentanyl and regulate sober living homes. In 2015, Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey (D) reached a $325,000 agreement with a naloxone manufacturer to provide naloxone to police officers and firefighters. Virginia Attorney General Mark Herring (D) recently launched www.HardestHitVA.com, an informational website that provides treatment resources and worked with a prescription drug manufacturer to provide 80,000 drug disposal kits.

Local Government Intervention

Perhaps closest to the crisis have been local governments, an example being Rio Arriba County, New Mexico, which reported an overdose death rate of 85 per 100,000 people in 2016. Cities such as Dayton, Ohio and Baltimore, Maryland report overdose death rates close to 40 per 100,000 people in 2016. In response to heighted overdose death rates, the National Association of Counties (NACo) and the National League of Cities (NLC) formed the City-County National Task Force on the Opioid Epidemic. The Task Force issued a report identifying the following solutions:

- Facilitating safe disposal sites and take-back days;

- Referring individuals to community-based drug treatment programs as an alternative to incarceration; and

- Securing discounts on naloxone and MAT drugs through purchasing programs for state and local agencies.

How Can the Commission Incorporate these Policies?

The final report to the President will likely contain a wide range of actions for federal, state and local actors to initiate. For example, Governor Christie has urged the federal government to remove the prohibition on federal Medicaid funds to be used for “Institutions for Mental Disease.” Under existing law, federal Medicaid funds cannot be used for individuals receiving inpatient substance abuse treatment in a facility with 16 or more beds. Governor Christie has stated that removing the prohibition would allow the state to double the amount of Medicaid beds that could be used for treatment.

In addition, the 21st Century Cures Act allocated $1 billion over two years ($500 million this fiscal year and $500 million for the next) for state grants to address opioid abuse, prevention and treatment. Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price, M.D. recently issued the first round of that funding, totaling $485 million. Quite simply, the Commission’s focus may include recommendations for the best way states can spend these funds. Secretary Price also sent a letter to governors stating, “I will seek your assistance to identify best practices, lessons learned and key strategies that produce measurable results.” Furthermore, two of the four state representatives on the Commission are from states that have not expanded Medicaid - Florida and North Carolina. These grants are especially important for non-expansion states because it provides an additional source of funding - about $27 million to Florida and $15.5 million to North Carolina - for treatment and recovery programs.

Finally, a lack of standardization in each state’s PDMP and how they are used could be a focus area as well. According to an article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), the median PDMP registration rate among prescribers is 35%. Further, a CDC report gave 43 states a low rating because prescribers are not required to consult the PDMP before initial opioid prescriptions or to conduct subsequent checks every three months. Such variance requires the action of state and federal leaders to ensure PDMP use requirements do not burden the delivery of health care and instead prevent opioid misuse and diversion.

Conclusion

The Trump Administration has signaled with this Commission that addressing the opioid crisis is a priority and one requiring the collaboration of federal, state and local leaders. The inclusion of Governors Christie, Baker, Cooper and Attorney General Bondi presents an opportunity for state successes and lessons learned to inform the national conversation. As these policies progress, and their impact on state and federal policy assessed, we as the leader in state government relations will keep you informed as the interim and final reports are published.